This work was funded by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) as part of the Neighbourhood Battery Initiative (NBI)

Welcome to the Neighbourhood Battery Knowledge Hub!

This Knowledge Hub was created in 2022. Please note that the information contained on this site may no longer reflect the latest information or best practice guidelines.

What is a neighbourhood battery?

It’s a mid-sized battery (bigger than a household battery, smaller than a big grid-scale battery), about the size of a few fridges side-by-side up to the size of a shipping container. It can sit in the local electricity network in a suburb or it could be connected to a particular building, like a factory or a shopping centre.

Why neighbourhood batteries?

In response to climate change, our electricity system is gradually transitioning to an energy system based on renewable energy (e.g. solar and wind power). Like all big transitions, there are a few challenges. One of these is that renewable energy (wind and solar), isn’t available all the time (it’s intermittent). In particular, solar energy is greatest during the day, whereas we need electricity in the morning and in the evening. If only there was a way to store the daytime energy for later use…

This is why people are excited about neighbourhood batteries. They can store energy from our rooftop solar panels during the day for use when we need it in the evening (this is sometimes called ‘solar soaking’). Other storage options, like big batteries and pumped hydro, can also help with this; but neighbourhood batteries could do this near where the solar is produced, which is more efficient than sending it away to be stored. A neighbourhood battery, which could store the solar power from dozens of rooftops, is also more efficient than every house having their own battery. What’s more, it could make this local renewable energy available to people who can’t have their own solar panels.

What about community batteries?

The terms community battery and neighbourhood battery are often used interchangeably, but we consider community batteries to be those that involve the community. This could mean the community owning the battery, making decisions about how it’s designed and run, actively participating in energy exchange with the battery, or receiving particular benefits or services from the battery. A local council could own a neighbourhood battery to improve energy affordability and lower greenhouse gas emissions, for example. If these benefits were focused on the local community and the community was involved, we would regard this as a community battery.

In contrast, an electricity network business could own and manage a neighbourhood battery as part of local grid infrastructure. In this case, the battery could help to balance supply and demand and stabilise the grid. Or it could be owned by an energy business that sells the electricity on energy markets (note that businesses would need a lot more than one neighbourhood battery to do this). In both cases, this would not be a community asset, unless the community is involved, even though these businesses could pass on benefits to customers.

Community batteries do seem to make a lot of sense in helping us to transition to a more sustainable energy system. They are also exciting because of the promise of social benefits, potentially allowing us to share renewable energy, work together to act on climate change, and develop models for collectively managing resources. But before we get too excited…

It’s not simple

Our electricity system used to be a centralised one, with energy being produced in distant locations (power plants) and transported to (almost) every household. Now that a lot of us have solar panels, we are seeing it become a lot more decentralised. We can now generate our own solar energy and use it in our homes to heat our water and run our appliances. Energy we don’t use can be exported to join the ‘pool’ of electricity (electrons) in the grid, flowing to where it is needed. Managing flows between all the places where electricity is produced and all the places it is used is a massive and complicated exercise, carried out be network businesses and overseen by governments.

It’s important to be aware that a neighbourhood battery is connected to this wider grid, not just the local neighbourhood. This means it is not restricted to just charging off solar energy that is generated locally. If there is surplus solar energy from households nearby (within that local network) then the battery will charge off that surplus solar. If there isn’t, for example, if we charge a neighbourhood battery at night, it will absorb electricity from a distant (coal or gas) power plant.

Also, the battery is unlikely to meet the electricity needs of the neighbourhood, so households will still need to get electricity from the grid. Some people are interested in how neighbourhood batteries could supply power when communities get cut off from the grid, for example during emergencies like bushfires. It turns out that this scale of battery, even if there are a lot of solar panels around, is quite limited in how much it could provide in these circumstances (generally less than an hour of power to the whole community or several hours if restricted to a single site like a community centre). So for this use, you will need a larger battery.

This demonstrates that a neighbourhood battery forms just a part of the larger electricity system, a system which is in flux, and needs to be constantly managed to balance supply and demand safely. The battery needs to be integrated into this system in order to contribute to this balance safely and reliably.

So, neighbourhood batteries are a great idea, but they are complicated and also – at this point in time – expensive.

So why aren’t there more neighbourhood batteries in Australia?

It’s true, neighbourhood batteries are quite a recent thing, and there aren’t many installed (less than 20 in Eastern Australia in 2022). This is because, as above, they’re a complicated technology embedded in a complicated system. Because it is early days, this scale of battery is expensive (starting at around $200 000) for the battery itself plus control gear). This will hopefully change if more are installed.

In addition, because of the complexity of integrating them into the energy system, neighbourhood batteries need to be installed in partnership with local network businesses known as Distribution Network Service Providers (DNSPs). These businesses are used to handling their own assets, and it’s not straightforward for them to support community battery projects, especially if communities don’t have an understanding of what’s involved.

We hope these guidelines will help.

What are these guidelines and who are they for?

These guidelines have been created by researchers at the Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program at the Australian National University, as part of the Neighbourhood Battery Initiative (NBI) under the Victoria Government Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

The guidelines are intended to provide information and guidance to:

- Community members or groups who’d like to find out what is involved in developing a neighbourhood battery

- Community members or groups who need guidance on setting up a neighbourhood battery project, including feasibility testing and implementation

- Local councils and other levels of government who want to support or be involved in neighbourhood battery projects

- Energy businesses, including distribution network service providers, generators and retailers who may be interested in neighbourhood batteries, particularly if they want to engage or partner with local communities

- Other businesses such as developers, shopping centres or large organisations like aged care facilities who might consider installing a neighbourhood battery

The guidelines are written for the Victorian context. So, some of the details won’t apply elsewhere, particularly legal and regulatory requirements. However, most of the guidance is relevant across the National Electricity Market in Australia (the East Coast) and beyond.

Because neighbourhood batteries are relatively early in their development, there is still a lot we don’t know about them. We have created the guidelines to allow a wide variety of different business and operational models. This way, we can keep learning together and from each other.

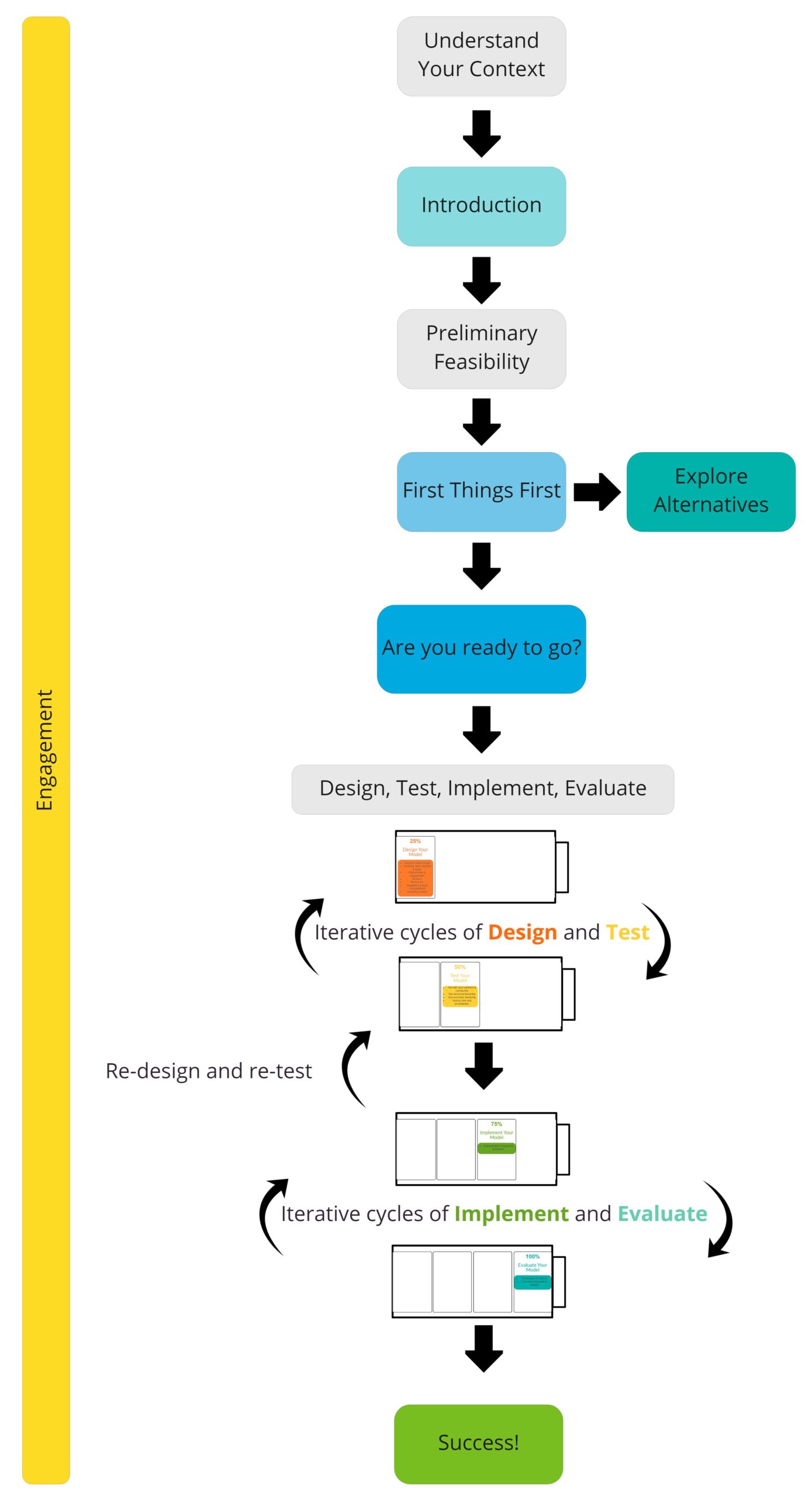

How you engage with the content of the knowledge hub will vary depending on who you are, what organisation (if any) you represent, and what stage you’re up to in your journey. The structure of the knowledge hub and our intended journey through its contents is shown below. However, you can also find information by clicking on particularly sections or using the search function.

In providing these guidelines, we want to emphasise that a neighbourhood battery project is not a straightforward and simple process. It is challenging, time consuming and will require money, partners and resources. We have therefore provided information to help you decide whether a neighbourhood battery is the right option for you, and what alternatives exist.

We wish you luck on your neighbourhood battery journey!

The Knowledge Hub Creators

Dr Wendy Russell

Research Fellow

Dr Wendy Russell is a transdisciplinary pracademic. As a research fellow in BSGIP, she brings her interests in responsible innovation, assessment and governance of emerging technologies, and public engagement to research on energy transitions. Wendy is also an engagement practitioner, worked for a time in the Commonwealth Department of Industry, Innovation, Science and Research, and before that was an academic at the University of Wollongong.

Louise Bardwell

Research Assistant

Louise Bardwell is a research assistant in the Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program in the School of Engineering at the Australian National University with a background in renewable energy engineering and Pacific/Asian studies. She is interested in transdisciplinary research pursuing the rapid decarbonisation of our energy systems through the use of renewable energy technologies.

Dr Hedda Ransan-Cooper

Senior Research Fellow, research leader

Dr Ransan-Cooper is Senior Research Fellow at the Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program at the Australian National University. She is an environmental sociologist with an interest in householder experiences of storage and grid integration and the governance of energy transitions. She has worked in partnership with government, industry and community groups on technologies such as neighbourhood batteries, grid integration technologies (such as virtual power plants) and microgrids. She is interested in distributional questions, and on questions around how to bring inclusivity and justice into the way the energy transition is governed.

Dr Marnie Shaw

Associate Professor, research leader

Dr Marnie Shaw is an academic in the School of Engineering at the Australian National University and a researcher in the Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program. Her research interests focus on the integration of energy storage across the whole energy system, to support rapid decarbonisation.