Now that you are committed to going ahead or at least to further exploring the prospect of a neighbourhood battery, you need to revisit the need and purpose. If you’ve set up a project team, it’s good to make sure you’re all on the same page about why you want a neighbourhood battery (the purpose), what you want it to achieve (goals), and whether there is a need. As a neighbourhood battery is part of the wider electricity system, which provides an essential service to the wider community, you need to think broadly about purpose, and particularly about the broader needs that the battery might serve.

Note that your needs and purpose may be best served by a series of batteries in your region, or by joining other groups to establish a network of batteries. Networks of batteries potentially provide economies of scale which may make your battery project more feasible. In the rest of this section, we generally refer to single batteries, for simplicity and because each battery in a series needs to be grounded in a particular community or setting. In general, the design considerations discussed here are all relevant to series of batteries. Other aspects of ‘scaling up’ will become clearer as more such projects are implemented.

As part of establishing your project, you will be making new partnerships and relationships. It’s really important that they understand your purpose and the need you seek to fill, that they agree that these are good reasons to consider a neighbourhood battery, and ideally that they have an opportunity to give their own perspective. They may challenge the need and purpose that you’ve articulated, and this is likely valuable, because meeting multiple needs is important for feasibility. This is also an important aspect of getting buy-in from your partners, and potentially the wider community of people involved.

For example, you might live in a neighbourhood with a lot of solar panels, and you get together with some like-minded neighbours to consider putting in a neighbourhood battery to provide a mechanism for self-consumption and sharing of solar energy within the neighbourhood. You might go ahead assuming that there will be a need and an interest in this self-consumption and sharing. Without testing this assumption, however, you might get to a stage when you want people to sign up to the battery, and only then discover that many of your neighbours have plans to buy electric vehicles and to use their storage potential to enable self-consumption. They may not want the complexity of being involved in a neighbourhood battery. Or you might find that there is a need for EV charging that the battery could provide, which would need to be factored into the design. This example highlights the importance of early engagement to understand the beneficiaries and their needs and constraints (see Engagement).

Part of thinking about need and purpose is also understanding how a neighbourhood battery fits into a broader vision of the energy transition. Energy systems are changing rapidly, and our local plans and actions are part of a broader transition; they are pieces in a larger puzzle. Whether you are a community energy group or an energy business, it makes sense to think about how implementing a neighbourhood battery might be part of the change you think needs to happen, and that the community thinks needs to happen. Thinking about how your project fits into broader transitions might change the way you design and plan your battery project.

Core values and beneficiaries

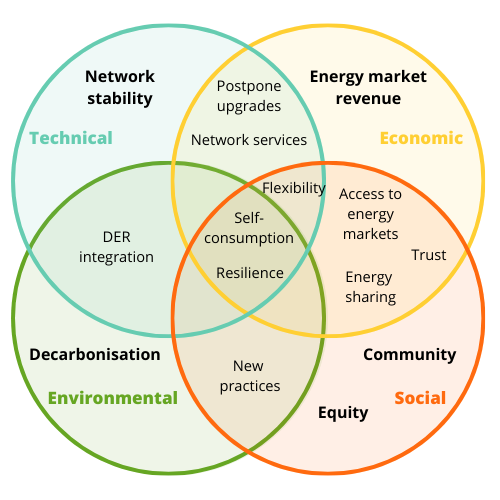

Your neighbourhood battery must provide benefits or values that make it worth the investment and can sustain the ongoing operation, maintenance and repair of the battery rush. These will often include public values, such as mitigating climate change and community development, as well as benefits to individuals or organisations, like lowering electricity prices or autonomy in storing their solar energy. Many of these values are worthwhile in themselves, but a neighbourhood battery is an expensive asset, so some of the values need to generate revenue to cover the cost of the battery, including ongoing operating costs. Note that many people are prepared to pay for environmental and social values, so don’t assume that people are only motivated by financial returns. However, understanding what people value and are prepared to pay for is a critical part of understanding whether your battery project is viable.

In this section, we’ve listed core values first and beneficiaries second. The values connect with your purpose and goals, and the need is connected with beneficiaries. Getting clear about your core values will help to identify who the beneficiaries might be, and how your battery project connects with what they want and need. Having developed a deeper understanding of beneficiaries, you need to double back and make sure your core values resonate with what they value.

Core Values

Consider the benefits of neighbourhood batteries. Think about the benefits and values you want your battery to provide based on the need, purpose, and goals you’ve articulated. Try to identify all the things that you’d like from the battery, but also which are most important to you. Chances are, you won’t be able to achieve all of the benefits you’d like, and there will be trade-offs. Return to your need and purpose and list your core values that will meet the needs and aspirations of the people who the battery is intended to serve.

Articulating your core values is your value proposition. It tells people what you are offering and what needs you propose to meet. You should test your value proposition with potential beneficiaries at this stage. This includes getting an idea of what they might be willing to pay and do (e.g. changing electricity providers) to gain these benefits.

Beneficiaries

Who is the battery for? Beneficiaries may be people who will pay for battery services i.e. customers, who may pay for use of the battery in some way. It may include utility businesses that could value and pay for the services the battery provides. It may also include people who join up to be part of the battery project, including you, the project team. You might also consider people or organisations who you could give benefits to. For example, you may choose to give surplus energy or profits from the battery to a community centre or school. Finally, you might also want to consider things like the electricity grid, a low-carbon energy transition, the environment, and future generations as beneficiaries of the battery.

Ultimately, the benefits and services of your battery must generate enough revenue to match the costs of the battery project, including loan repayments, operation, maintenance and repair as well as contingency if the battery is offline or wholesale prices consistently spike when the battery usually charges. Currently, revenue from the energy market and network services are unlikely to cover costs, so additional finance will be needed. This could be in the form of grants or funding from bodies who value battery benefits.

Your battery will be storing and supplying energy as part of the electricity system in your community. Electricity is an essential service, and it’s therefore important to think about equity when you’re considering beneficiaries. Historically, transitions to renewable energy have tended to favour certain groups (who can afford new energy technologies and/or own their own home). Neighbourhood batteries provide important opportunities to redress this imbalance. Depending on the business model, the battery can provide access to renewable energy for people who have traditionally been excluded. People should be able to benefit without active engagement. Many householders are not engaged in or interested in participating in retail tariffs. It’s important to consider these people and how they will benefit from the battery.

Juggling core values

Some of the values the battery can provide are in direct tension with one another. At the moment, for example:

- Market participation vs decarbonisation – maximising market revenues could lead to charging at times when electricity is cheap but not renewable (e.g. at night, when coal power continues to supply the bulk of our electricity). The battery operator can choose not to charge at night, but this may reduce revenue.

- Backup power vs market participation – could be in tension if power is reserved for backup rather than earning market revenue. However, priorities can be set according to conditions so the battery management system could prioritise backup power in the case of extreme weather or high bushfire risk.

Although it is critical that your battery project is financially feasible, if the model you adopt to achieve this doesn’t fulfil the purpose, goals, and needs that underpin the project, there’s not much point going ahead. In the extreme case, it is possible, for example, to set up a neighbourhood battery in such a way that it increases carbon emissions (see Environmental impacts) and exacerbates inequality. This highlights the importance of meeting the triple bottom line (economic feasibility, environmental sustainability, social justice). Note also, that goals and needs may change, or become clearer as you engage with your community and partners.