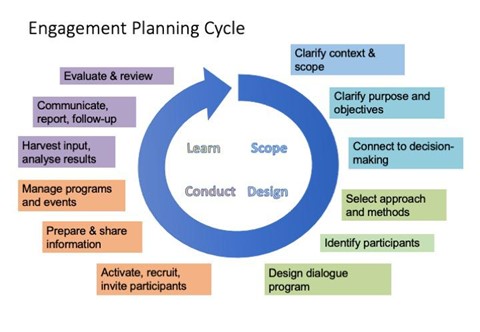

You need to develop an engagement plan early on. You’ll need to keep this flexible, and do more engagement planning as the project develops, as you learn about your community and the channels and activities that suit them best, and as things come up or go wrong (as they inevitably will!). In general, the better you anticipate the need to engage, the less reactive engagement you’ll need to do. The planning cycle below can be used to plan each engagement activity (especially the major ones), but can also be used for your overall engagement plan or strategy, which will involve a program (series) of activities.

Understand context and stakeholders

For any engagement, the importance of understanding context can’t be over-estimated. Understanding more about the people you’re engaging with, and their relationship to the issue, will enable you to tailor your engagement activities. Ask yourselves: Are there different cultural groups? Do you have retirees living alongside young families? Is there a mix of owner-occupiers and renters? Is there a mix of political progressives and conservatives? Who are the marginal people who will be hard to reach (this could include culturally and linguistically diverse communities, young people, disadvantaged people, and carers)? Are there disparate groups with different interests, who may not see eye-to-eye? For example, do you have a mix of ’sea-changers’ or ’tree-changers’ and long-term locals? For community energy groups, answering such questions will help you understand community needs, build your group, and gain support. This could do this systematically by mapping your stakeholders, which will help to identify partners, contributors and beneficiaries and also potential blockers – those who may either block or enable your project, depending on whether they are on board.

Remember that the place where you are considering setting up a neighbourhood battery is Aboriginal land, and the custodians of that land are a part of your community, who you need to engage with at an early stage. As well as potentially having concerns and advice about how the battery connects with caring for country, Indigenous Australians also have a history of being under-consulted and under-served by infrastructure projects and essential service provision, so taking account of their needs and concerns will build the public value of your battery project. We should also consider those without a voice at all, such as the environment, other species, and future generations.

It’s also important to understand the history of the issue for the community. Have there been energy or infrastructure projects in the community in the past? Were they controversial? What was the basis of the controversy? What sensitivities might exist as a result? How successful was engagement associated with past projects? This may tell you if there is already resistance or ’engagement fatigue’ in the community.

Clarify objectives

One of the biggest mistakes in engagement planning is to lead with tools, rather than objectives. So often, people turn to their favourite or most familiar engagement method, whether it’s a survey, a stall, a public meeting, or a deliberative forum, before they’ve got clear on why they’re engaging and what they want to achieve. No matter how well they implement the method, if it’s not the right method for what they’re trying to achieve, it won’t be effective.

So, spend some time, for your overall engagement plan, but also for each engagement activity, understanding the objectives and scope. Imagine what success would look like. What would you have achieved? This will help you develop evaluation criteria to gauge how effective the program was, and what you can learn for the future.

Clarifying objectives will also connect with understanding context. For example, early on, you may want to let people know about your project, and potentially get them excited about it. This would make sense if what you know of the community suggests that they will be receptive to a neighbourhood battery. However, if the community has had some history of controversy with infrastructure projects, your early objectives may be to understand sentiment in the community, and to carefully check in with people about their views on a neighbourhood battery. For the former, you want a method that will provide information, like a stall or presentation, but also a way for people to get involved, so you might sign them up to a newsletter, or you might set up a regular meeting like an energy cafe. For the latter, you might do a letter box drop explaining your proposal and inviting people to an interactive forum to discuss it. Or you might hold some kitchen table conversations to discuss the proposal.

Clarity around objectives can also be important for expectation management. Just as sometimes you will encounter resistance from the community, at times you may meet with a surplus of enthusiasm. Community members may think neighbourhood batteries are a wonderful idea and be ready to sign up immediately. Being clear about what stage you’re at with your planning, what questions and challenges remain, and what input you want from them at that stage, can help to channel enthusiasm and build realistic expectations and participation.

Connect to decision making

For all engagement planning, as well as clarifying objectives, you need to connect the engagement to decision making. Particularly for large organisations, your engagement activities need to be connected with decisions, including business model development and implementation. This includes a commitment from decision makers to take community input on board. In some cases, this may involve empowering the community to decide, e.g. about core values, customer participation models, or artwork for the battery. In other cases, this can be a promise to consider community feedback, ideally with a commitment to communicate how feedback influenced the decision.

The second part of connecting to decision making, then, is identifying what decisions are in front of your group or organisation, whether they be about the business model, the operational model, customer participation, or site selection, for example, and planning engagement to feed into these. This input needs to be integrated with other inputs such as team planning, feasibility studies, and constraints from regulatory contexts or from contributors. Taking a co-design approach, where beneficiaries are considered as partners in your design and planning, can help with integrating these inputs, and can help to avoid engagement being disconnected and out-of-sync.